Kylie Sweeney

Adolfo Camarillo High School | Camarillo, CA | 10th

Inspirational Family Member

My Great-Great-Grandmother

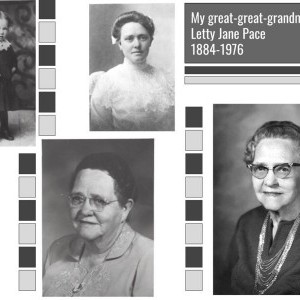

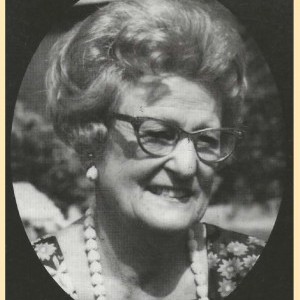

The first woman to vote in my mother’s adoptive family is my great-great-grandmother, Lona Reinertson. She was born on December 23, 1898, in Bode, Iowa to Chris and Anna Rivenes. She attended Normal training at Park Region College in Fergus Falls, Minnesota to become a teacher. Once she graduated in September 1918, she was hired by Andrew Reinertson who was the clerk of the school district. Lona was hired because of her friendship with Helen Oscarson (the clerk’s niece) and because Rudolph (the clerk’s son) thought she was quite beautiful. While working at the two-room school she earned about $60 a month and paid $30 for board and room at a farmer’s home. Throughout the rest of the year, Lona and Rudolph went on several dates growing closer as a couple.

Lona’s classroom had about forty children and was quite a handful but she managed. After the school year was over Rudolph and Lona could not picture themselves apart and decided that the only solution was marriage. They were wed on June 26, 1919, and moved into a small two-room homestead shack on a farm Rudolph’s dad built them. The fall harvest was poor for the second year in a row which prompted Lona and Rudolph to move to Vancouver, Washington on January1, 1920. Their first child was born on April 26, 1920 and they named her Lorna Rudelle, who is my grandma’s mom. Throughout the years the couple had six more children, two boys and five girls in all.

They moved to Burns, Oregon for a short time in the 1930s when their farm failed due to the economic pressures of the Great Depression. While they were in Burns, Lona managed the local newspaper distribution center for extra cash. Then in 1949, they moved to Eugene, Oregon where Lona ran a grocery store and raised their seven children while her husband went back to Burns to open a second store. After that business failed they moved back to Burns where they opened a shoe store which Lona helped with while participating in church activities. Both Rudolph and Lona retired to Portland in October 1973 after selling their shoe business.

Lona Reinertson died in Eugene, Oregon on August 29, 1978, due to cancer. During her lifetime Lona lived an overall happy life as a loyal spouse with a strong work ethic.

Historical Figure I Admire

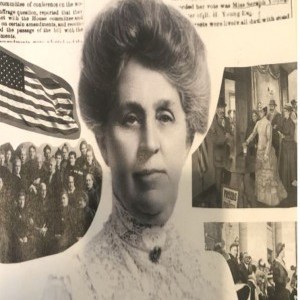

Emily Howard Stowe

Emily Howard Stowe was the first woman suffragist, principal, and medical physician in Canada as well as a Women's rights advocate. Emily was the firstborn out of six to Hannah Howard and Solomon Jennings on May 1, 1831. In 1846, Emily was homeschooled by her mother until she became a teacher at a one-room school in Summerville, Canada. For the next seven years, Emily taught in multiple schools across Canada receiving half the pay men earned. From 1853-1854, Emily attended Provincial Normal School in Toronto to obtain her education degree. After graduating with a First Class Certificate, she became the first woman principal in Canada while working for Brantford School Board from 1854-1856. At that point in her life, Emily was looking to settle down and was wed to John Stowe in 1856. Due to their marriage, she decided to leave her teaching position and had three children from 1857-1863.

Sadly, her husband was diagnosed with tuberculosis and sent to a sanitarium until 1873 when he returned healthy. While he was gone, Emily was forced to return to work as a teacher in order to finance her family of three. She then realized that the position did not produce enough money to support her family. So, Emily decided to pursue a career as a medical physician. At first, Emily was denied by Toronto Medical School so she ventured to New York Medical College for Women. There she earned her degree in homeopathic medicine. While attending school in New York she met a fellow suffragist, Susan B. Anthony, who taught her patient strategy. After she completed her schooling in 1867 she moved back to Canada where she set up a homeopathic medical practice in Toronto.

Emily being a woman was prevented from earning her medical license in spite of her medical degree. This forced her to return to school at the University of Toronto in 1870 where she studied for years to acquire her medical license. Later in her career, in 1880, Stowe was accused of being an abortionist when a pregnant woman died after taking medicine prescribed by Emily. Luckily, the crisis was averted and she was granted her medical license on July 16, 1880. After the return of her husband, her family uprooted and moved to Toronto where John and Emily both had their practices. Two of their three children followed their medical legacies; their son joined his father's dental business and their daughter became the first woman to be fully trained in Canadian medical school.

Succeeding in her medical career, Emily refused to let her egalitarian views be trampled by men in her society. So, she took to protest, debates, and lectures on women’s equality and right to work side by side with men. Emily’s outlook on women in the medical field was heavily influenced by Dr. Clemence Sophia Lozier who was also a fellow suffragist whom she studied under in New York. In 1877, Stowe founded the Toronto Women’s Literary Club to fight for the rights and improved working conditions for women. This club progressed through the years and evolved into the Canadian Women’s Suffrage Association in 1883 with Emily as one of the Vice presidents. That same year she also led the creation of Woman’s Medical College in Toronto. Emily’s main goal after her medical career was to ensure that women had the right to equality so the next generations of women did not have to struggle as she did.

In the end, Emily Howard Stowe was a triple threat who stormed Canada and changed its society’s views for the better. Emily died on April 30, 1903, leaving behind a legacy that was certain to be remembered. From teaching in Summerville to creating organizations for women’s rights Stowe lived an astounding life considering the time period. During the years Emily was alive, 1831-1903, women were viewed as inadequate to men and expected to live a certain way. However, she refused to conform to society's expectations and became a figure women could look to for aspiration. Her accomplishments allowed women in the medical career the prerogative to work alongside men, women’s right to vote, and overall equality for generations to come. Emily used her experience with misogyny to fuel her drive of helping other women accomplish their goals and speak up against societal norms. Along with proving every man wrong and becoming the first woman principal and medical physician in Canada.

What the Project Means to Me

This project widened my knowledge of women's suffrage and made me understand how hard these women fought so that I could have the right to equality. While researching Emily Howard Stowe I learned about Canada’s medical history. I was extremely shocked by how long it took women to finally be acknowledged in society. When researching my family history I was surprised by how independent and ambitious my great-great-grandmother was considering the societal norms of that time period. Through my research, I noticed that both Emily Howard Stowe and Lona Reinertson started as school teachers but ended up accomplishing so much more.

The ambition they both shared was incredibly moving and showed me that if you want something you have to fight for it because no one is going to do it for you. These women raised the standard for society's expectations through their work ethic, accomplishments, and legacies left behind. Both Emily and Lona helped their husbands when their family was struggling financially which was not something most women were able to do back then. These courageous, strong women were versatile in their work environment and could tackle anything that they faced. One of Emily’s contributions to society, Woman’s Medical College in Toronto, is still standing today and used by the women in Canada. This just goes to show how change no matter how small can make an immense development in society. Without Emily challenging the authority of men, women might not be allowed to practice medicine in Canada. Just as if my great-great-grandmother had not persistently aided my great-great-grandfather with the workload I might not be here today. Overall, this project allowed me to learn my family history and gain insightfulness of woman suffrage.

Explore the Archive

More From This Class

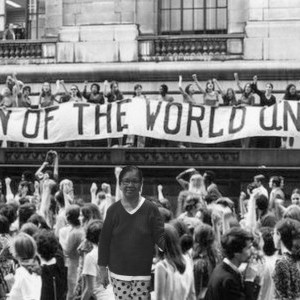

Click on the thumbnails below to view each student's work.Deadline Extended

There's still time to join Women Leading the Way.

Become a part of our storytelling archive. Enroll your class today.

Join the Project