Phoebe Brown

The Ellis School | Pittsburgh, PA | 11th Grade

Inspirational Family Member

My Great-Grandmother

In an interview with my maternal grandmother, I discovered that the first woman in my family to vote was her mother (my great-grandmother), Maude Helmick. She had turned twenty-one in 1920, and voted in that year’s presidential election. She lived on a farm in Moorefield, West Virginia, where she and her family kept dairy cows and bees, grew vegetables, and were almost completely self-sufficient.

In the election of 1920, she and her family would have walked or taken a horse and buggy together to the polls, which were several miles away. As a member of the rural lower class, it is likely that she and her parents voted for Warren G. Harding, who won that year with a landslide four hundred and four electoral votes, in addition to winning the state of West Virginia. She valued having the right to vote, seeing it as a honorable duty to take part in as a citizen. According to my mother, Maude Helmick admired Abraham Lincoln in particular for his policies and the good he did for the country during his time in office. This makes sense, as her family is from West Virginia, a state that formed during the Civil War by splitting from Confederate Virginia.

Maude Helmick’s positive attitude towards voting has affected my grandmother and my mother, who were equally enthusiastic about voting once they became old enough to vote. Though she wasn’t wealthy and didn’t have the means to become a politician, it is clear from my mother’s and grandmother’s reflection on her that she valued the nineteenth amendment, which gave her the right to take part in the system of electing representatives that was and remains a central part of the United States Government. I will vote for the first time in the presidential election of 2020, one hundred years after Maude and thousands of other women voted in America for the first time.

Historical Figure I Admire

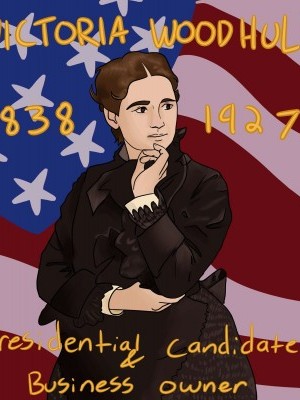

Victoria Woodhull

Victoria Claflin was born on September 23, 1838, in the small town of Homer, Ohio. She married Canning Woodhull at the age of only 15, divorcing him later but keeping the name. Her push for women’s rights began when she and her sister, Tennessee, met the railroad baron Cornelius Vanderbilt. He funded Victoria and Tennessee’s new business: the first women-run stock brokerage, which opened in New York City. Although funded by Vanderbilt, the brokerage was run solely by the two sisters. Newspapers were attracted by the uncommon sight of women being co-owners of a business that handled finances, and printed articles that called the sisters “Bewitching brokers” and doubted that these women were fit to run a business. Despite the bad press, Woodhull, Claflin & co. had good business, particularly with other women. The company had a ‘women’s only’ room in the back, where they could discuss finance with wives, teachers, and other female business owners privately. Victoria’s second husband, George Blood, also worked at the brokerage, managing the transactions. Woodhull, Claflin & Co. was moderately successful, but Victoria Woodhull had bigger things in mind for her future.

In the mid to late 1800s, there was a set of strict expectations placed upon women, which historians call the Cult of Domesticity. Women were expected to stay in the private sphere and uphold the values of piety, domesticity, purity, and submissiveness. The ideal woman in the Cult of Domesticity would care for the children, read only religious texts, respect all male figures — most of all her husband — and never hold any values that may be controversial. Victoria Woodhull, as co-owner of a business, didn’t conform to society’s expectations of her. Strongly supported by her second husband, she became an advocate for free love: the right for women to love, marry, and divorce whomever they want. As a result of rejecting the gender roles of the century, she was demonized in the press. In Harper’s Weekly, she was depicted as the devil in a cartoon by Thomas Nast, called “Get Thee Behind Me, (Mrs.) Satan!” with the caption “Wife (with heavy burden). ‘I’d rather travel the hardest path of matrimony than follow your footsteps.’” Still, Woodhull pressed on. She published a journal with her sister, "Woodhull and Claflin’s Weekly", that promoted her radical agenda, and when that wasn’t getting her the visibility she wanted, Victoria took her ideology and put it to the test.

In 1871, Victoria Woodhull announced that she would be running for president in the upcoming election. Although she did not yet have the right to vote, there was no banning of female presidential candidates in the Constitution. In her essays entitled The Origin, Tendencies, and Principles of Government, she wrote: “While others argued the equality of woman with man, I proved it by engaging successfully in business; while others sought to show that there was no reason why women should be treated, socially and politically, as being inferior to man, I boldly entered the arena of politics and business and exercised the rights I already possessed. I therefore claim the right to speak for the disenfranchised women of the country, and believing as I do that the prejudices which still exist in the popular mind against women in public life will soon disappear, I now announce myself as candidate for the Presidency.”

Unfortunately, Woodhull received no votes in the 1872 election against Ulysses Grant, simply because she was 34 years old instead of the constitutionally mandated 35. Though she didn’t come close to winning, she was a role model for future suffragettes and women in government for years to come.

What the Project Means to Me

Before writing these essays and researching, if someone asked me when the first woman ran for president, I probably would have said sometime around the 1950s or 60s. Learning that Victoria Woodhull ran for the presidency in 1871 was really interesting, especially considering that she was actually ineligible to run because of her age. Just by getting media coverage, whether that be positive or negative, Woodhull raised awareness of the lengths women would and did go to in order to get voting rights. It’s unfortunate that women in America had to wait another fifty years after Woodhull’s candidacy to get the basic American right to vote. Like Victoria Woodhull, the first woman in my family to vote viewed partaking in the American democracy as an honorable duty.

Maude Helmick, my maternal great-grandmother, passed down the value of voting to my grandmother, my mother, and me. From her and Victoria Woodhull, I know that the best way to get inequalities within our government and laws righted is to get out and do what you can, whether that be voting or marching and exercising free speech. I’m excited to vote for the first time in 2020, on the hundredth year anniversary of when Maude Helmick and millions of other American women voted for the first time.

Explore the Archive

More From This Class

Click on the thumbnails below to view each student's work.Deadline Extended

There's still time to join Women Leading the Way.

Become a part of our storytelling archive. Enroll your class today.

Join the Project