Lela Krackow

The Ellis School | Pittsburgh, PA | 11th Grade

Inspirational Family Member

My Great-Grandmother

Selda Goldman, the mother of my grandmother on my father’s side, was born in 1914, six years before women gained the right to vote in America through the 19th amendment. By the time she was eligible to vote in 1932, women had been voting for 12 years; unfortunately, I know little family history about Selda’s mother Minnie Bernstein, so Selda is the first woman on that that side of my family who I can confidently say voted. She married in her early twenties to my great-grandfather, Isadore Goldman, who owned an advertising business, but she never worked outside the home herself. However, my grandmother emphasized that her mother was a “modern” woman, so evidently, she considered one of the habits of a modern woman in the first half of the 20th century to be voting. Despite this fact, my grandmother recalled that Selda was not particularly vocal about exercising her right to vote and never explicitly encouraged my grandmother to do so.

This dramatically contrasts the situation I am in now with my own mother. Since I’ve been in middle school, both my parents, but especially my mother, haved stressed the importance of exercising my right to vote when I become eligible. My mother has always told me that I am to vote in every election, including the local ones, and that it is every citizen’s civic duty to do the same. I am highly anticipating my first visit to the polls when I am eighteen and look forward to being able to contribute my opinion to local and national issues. I wish there was a record of how my great-grandmother, who was alive during the height of the women’s suffrage movement, felt about the first time she walked up to an election poll, and I wonder if she experienced the same excitement I know I will.

Even though much is still unknown about my great-grandmother’s experience as a voter, the chance to explore the women in my past has succeeded in giving me a new appreciation for the expectations upon me that I will claim my right to vote, a right that I would not have had a century ago.

Historical Figure I Admire

Alva Vanderbilt Belmont

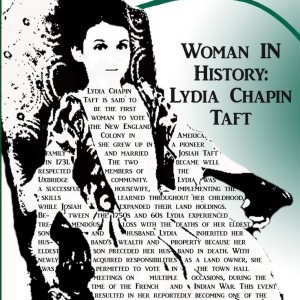

Alva Vanderbilt Belmont was one of the most influential benefactors and leaders of the women’s suffrage movement in the early 20th century. Her immense wealth, extensive connections, and commanding personality supported her successful role in the movement. Alva was born in 1853 in Mobile, Alabama to a wealthy cotton broker, and moved to New York as a child.1 A few years later after President Lincoln’s assassination made the state a hostile environment for their southern family, they relocated to Europe where Alva received the bulk of her education.2

In 1875, Alva Erskine Smith married William Kissam Vanderbilt, whose family had one of the largest fortunes in America at the time. Although the two were said to be immensely incompatible, their marriage succeeding in restoring her family’s financial and social status after their return to America.3 Eventually marital strife caused Alva to divorce William on the grounds of adultery in 1895, a decision considered to be “remarkably daring” for the time.4 The autonomy she sought to claim rejected the confines of the gender hierarchy and reflected “her need for independence and self-determination… strong enough to overcome social convention and expectations of wifely duty.”5 Alva’s vehement belief in the importance of female self-reliance and rejection of dependence on men would fuel her later engagement in the suffrage movement.

Shortly after her divorce, Alva remarried with socialite Oliver Hazard Perry Belmont and enjoyed a far more harmonious marriage with him until his death in 1908.6 It was at this time that Alva began to emerge as a prominent promoter of women’s rights. In 1910, she founded an organization in New York under the National American Women’s Suffrage Association (NAWSA) called the Political Equality Association.7 However, in 1914 she split with NAWSA and began collaborating with fellow suffragist Alice Paul at the National Woman’s Party (NWP). A great hobby of Alva’s was building and decorating mansions, and one of her houses in DC, known as the Alva Belmont House, even became the NWP headquarters. Other properties of hers, such as the Marble House in Newport, Rhode Island, became regular meeting places for women activists and were often the sites of widely publicized conferences that helped the suffrage movement maintain national interest.8 She further used her vast wealth to support various suffrage related endeavors, such as the shirtwaist strike in 1909.9 Yet Alva’s involvement went beyond simply providing funds; she was an active strategist and speaker and was experienced on the picket line. Her commitment as well as her financial contributions to the movement defined her as a leader among women suffragists, and she was appointed president of the NWP in 1920.10

By the mid 1920’s, Alva was spending most of her time in France, but she continued to extend her involvement with women’s rights abroad by creating the International Feminist Committee.11 Even after the passage of the 19th amendment that granted women the right to vote, Alva persisted in her activism, advocating for full political equality for women. She observed the right to vote as a new “tool” for women who still had a long way to go before they truly reached a position of equality.12 Alva was committed to making progress towards this goal until her death in 1933, and she is remembered as one of the great forces of the women’s suffrage movement.13

SOURCES +

What the Project Means to Me

At a young age, when I first learned about the concept of voting—in the most basic terms and the most general context—I took for granted the ease with which I assumed this activity to be one in which I would one day engage. It would be a while before I would gradually incorporate the knowledge of women’s suffrage, constitutional amendments, and the complexity of politics into my understanding of voting. In researching the stories of prominent women suffragists and the female relatives that have preceded me, I’ve supplemented my comprehension of this important part of our country’s history, which has given me a new appreciation for the right I possess to vote.

I am appreciative not only for the struggle of the women before me to secure this right for future generations, but for the mentality with which I’ve been raised that has taught me the civic importance of voting.

I think that while we can celebrate the suffrage granted to women a century ago, the discussion of this topic is not complete without mentioning the struggles citizens still face with respect to voting rights today. While my parents have always pressed that it is my civic duty to vote, a duty which I look forward to fulfilling, not all citizens have equal ability to civically engage. Voter suppression, which targets minorities and historically marginalized populations in particular, is a major issue in current day politics. While we no longer have to fight the battle of lifting voting prohibitions based on race or gender, voter intimidation and harassment, unnecessarily strict voting ID and ballot requirements, poll lines and closures, gerrymandering and more, all contribute to inequalities on the American voting landscape. This exploration of the history of women’s suffrage emphasizes the potential we have to make more progress towards even greater equality with respect to voting in America.

Explore the Archive

More From This Class

Click on the thumbnails below to view each student's work.Deadline Extended

There's still time to join Women Leading the Way.

Become a part of our storytelling archive. Enroll your class today.

Join the Project