Maggie Ginter-Frankovich

The Ellis School | Pittsburgh, PA | 11th Grade

Inspirational Family Member

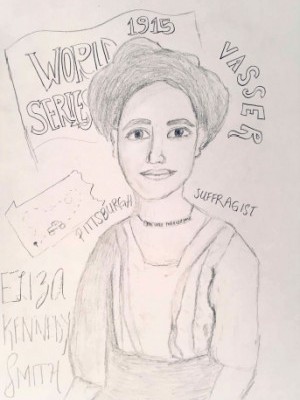

Eliza & Lucy Kennedy Smith

My grandfather not knowing too much about his mother’s voting, I turned to Eliza Brown for her story. She sat with me in her basement and showed me pictures of her grandmother, Eliza Kennedy Smith while she told me about Eliza Smith and her great-aunt, Lucy Kennedy Miller. Both graduates of Vassar, they became suffragists; non-radical women who fought for the vote. The sisters had rnany interesting tactics to try and convince women to vote in Pittsburgh. In 1915 during the World Series, they used an arcade where they broadcasted the scores of the game. They drew over 10,000 people per day, and when there was no game going on, they were the ones pitching—they were pitching suffrage! I found their outgoing and creative method of gaining support was pretty amazing.

Even in their busy lives as mothers and wives, they found time to rent a truck and drive across all of Pennsylvania where they canvassed on street corners, steel mills, to whoever would listen. That is how passionate I hope to be about the issues that I feel strongly about! What I felt was different about these women, was that although they voted conservative Republican, they fought for the justice of all. The suffrage movement in Pittsburgh was generally more integrated than most other cities, with some African American women being on the planning committee of a parade in 1914. Eliza and Lucy considered themselves non-partisan in the destruction of corruption in office, and ran the last (and corrupt!) Republican mayor (in Pittsburgh) out of office in 1933, even though they were Republicans. Their strong commitment to women’s suffrage and fair government was sparked by their education in philosophy, political science, and history. Eliza Brown relays to me that she believes the ideology of the Progressive Era, in which there was a desire to improve the world with humanitarian action, strongly influenced her grandmother. I agree—these women’s efforts to make all of our lives better is truly inspiring and is a strong reminder that the betterment for all is always rnore important than parties or politics.

I hope to carry with me when I begin voting the sisters’ spirit of determination and resilience and to use my vote with appreciation for all that they did for the movement. Like Eliza Kennedy Smith, I plan on using my education to make smart, calculated and humanitarian choices when I finally get to use my vote.

Historical Figure I Admire

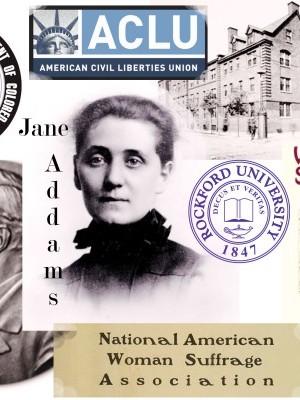

Jane Addams

A strong and forward-thinking woman, Jane Addams was at the forefront of the women‘s movement for equality in the late 1800s and early 1900s. Raised by a father involved in local politics and friends with Abraham Lincoln, Addams became intelligent and hardworking. After graduating from Rockford Female Seminary as valedictorian, Addams went on to study medicine.

After becoming ill during her studies, she travelled to Europe where she and her friend Ellen G. Starr visited a settlement house in London‘s East End: Toynbee Hall. This experience pushed her to open her own version in America and in 1889, Addams and Starr leased a house in Chicago, naming it Hull-House after Charles Hull, the builder of the house. The house served as a safe space for the community to learn and grow, and sheltered the poor, and many immigrants. Addams writes in Twenty Years at Hull-House, “In time it came to seem natural to all of us that the Settlement should be there. If it is natural to feed the hungry and care for the sick, it is certainly natural to give pleasure to the young, comfort to the aged, and to minister to the deep-seated craving for social intercourse that all men feel (109)." They added a gymnasium, a swimming pool, an art studio, and a public kitchen, as they were serving 2000 people a week by the second year. But Addams' work to improve her community did not stop there; she worked to eliminate child labor, reduce working women‘s hours, and create courts for juveniles. Addams wanted equal opportunities for all, and for women to have the vote. She supported Theodore Roosevelt, an advocate for women‘s suffrage. In 1905, she was elected to the Chicago Board of Education, and in 1908 founded the Chicago School of Civics and Philanthropy. Addams became the first woman president of the National Conference of Charities and Corrections where, even throwing herself into the position of a garbage collector, she worked tirelessly in her investigations for fairness. Not only did Addams want women to have the vote, but she desired that they have the same opportunities as men, to have aspirations and be able to accomplish them. She was vice president of the National American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA) from 1911 to 1914, and also a founder of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) in a time when many white women were just as racist as white men. Addams also rejected the conventional standard of marriage and motherhood, instead focusing on her goals.

A supporter of equal rights, she helped form the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) in 1920. Also a strong advocate for peace, she served as an assistant to Herbert Hoover where she provided food and relief supplies to women of enemy countries. Detailed in her book Peace and Bread in Time of War (1922), she explains that “peace and bread had become inseparably connected in [her] mind“ (Addams viii). In 1926, she suffered a heart attack, and her health never fully returned. On the same day she was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize, Addams was hospitalized and she died a few years later in 1935.

Jane Addams’ accomplishments and actions truly speak to both her beliefs, and her dedicated service. She spent her entire life working for the good of others, and not simply women. Her time at Hull-House, NAWSA, the NAACP, and in the White House demonstrates the vast range of her influence. Addams truly embodied the women's movement for equality, because she worked for the good of everyone, regardless of age, race, or sex.

SOURCES +

What the Project Means to Me

After sitting with Eliza and hearing her story, and researching Jane Addams in depth, I was amazed at how engaged and powerful these suffragists and suffragettes were. But this process also reminded me that the everyday women fulfilling their duty to America—and to the suffragettes and suffragists—by voting, are just as important. Each and every one of them fought for our freedom to choose who we want to lead us. I feel the best way to honor all of them is to vote. For me, learning about the history of the movement gave me appreciation for women who paved the way for us, and reminded me of the role I play. I’ve heard younger people say, “but why does it matter? We don’t even directly elect the president!” But it is an incredible privilege to have a voice and a say, and so it does matter!

Reading how Jane Addams fought for equality on all fronts, and how Eliza Kennedy Smith and her sister Lucy Kennedy Miller rallied the suffrage movement in Pittsburgh gave me deep appreciation for the vote. And sure, maybe the system today is not perfect. Maybe it should be changed, or maybe it shouldn’t. But the stories of these women shout that change is possible. They’ve granted us with one of the most powerful tools of change. We can vote in new representatives that can change the laws, and we can vote in a new president. And though it might seem that one vote is worth nothing, the success of the women and men who individually fought for the vote proves that millions of single voices can make real change. And so I plan on going into my first election ever with an open mind, a thankful heart, and the understanding that I’m honoring Jane, Eliza and Lucy’s legacy with my vote.

Explore the Archive

More From This Class

Click on the thumbnails below to view each student's work.Deadline Extended

There's still time to join Women Leading the Way.

Become a part of our storytelling archive. Enroll your class today.

Join the Project