Alena Lateef

The Ellis School | Pittsburgh, PA | 11th Grade

Inspirational Family Member

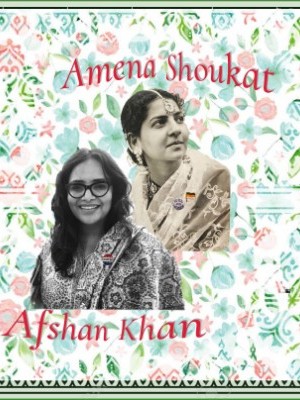

My Aunt & My Grandmother

Within my family, my aunt was the first woman who was able to vote here in America. During 1970, the paternal side of my family immigrated from India to America. While my paternal grandmother did not have the right to vote then, her daughter being an American citizen did.

My aunt, Afshan Khan was born in Houston, TX, during 1973. My aunt told me that, back then, she knew the importance of voting in elections, especially as an Indian Muslim woman. When she was able to enforce her right, she voted in the election of 1992 with the candidates Bill Clinton and Al Gore against George H. W. Bush and Dan Quayle. On the maternal side of my family, my grandmother Amena Shoukat was the first woman to vote. Born during 1940 in Hyderabad, India, my grandmother was born when India was still under British rule.

In personal interviews with my family members, I was told about how my grandmother remembered when the Nizam of Hyderabad, Mir Osman Ali Khan, would walk down the streets. My grandmother, along with the rest of the city residents, would have to stand up and cast their eyes downwards as a sign of respect when the Nizam walked by. When my grandmother was seven, India gained independence and granted both men and women the right to vote. She was able to vote in the election of 1962 between candidates Sarvepalli Radhakrishnan, Chowdhry Hari Ram, and Yamuna Prasad Trisulia.

From personal interviews, I have been told that my grandmother was more involved in Indian politics than other women during her time. In India, the act of voting was considered a big deal among women. It required finding another person to go with you, getting properly dressed, and riding in an auto-rickshaw to the booths. These tasks may sound menial in America, but in India, it required a lot of communal effort. Nevertheless, my grandmother was excited to implement her right to vote. I wish I could personally ask my grandmother about her experience voting in India, especially since there is not much documentation or retelling of these occurrences. However, since her passing five months ago, I can only rely on these precious personal interviews from my family in India.

Historical Figure I Admire

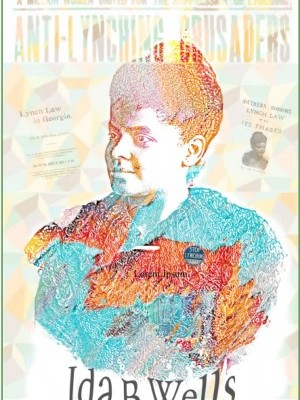

Ida B. Wells-Barnett

Ida B. Wells-Barnett was an influential, social reformer who never backed down from her beliefs, and demanded change for blacks citizens even as America was filled with violence and disorder. Born during the civil war on July 16th, 1862, Wells-Barnett was a slave for her first two years within Holly Spring, Mississippi. Although Wells-Barnett’s socioeconomic status was low—her being the oldest of eight children—her parents, interested in post-war Republican ideals, made an effort to provide her a good education.1 However in 1878, disaster struck; yellow fever spread to her town, killing her parents and brother.2 At the age of fourteen, Wells-Barnett taught at a county school in order to support her family. Later moving to Memphis, Tennessee, Wells-Barnett studied at Rust College. Then in 1884, Wells-Barnett was forced from her first class seat on a train.3 Uncomplacent, Wells-Barnett went to court; although she did not win, she stood up for black women’s rights. After this spark of activism, Wells-Barnett quit teaching and began working at a black newspaper where she wrote articles tackling controversial subjects like sexism, racism, and violence against women and blacks. After the lynching of three close friends, Wells-Barnett was propelled into researching white mob violence. Wells-Barnett’s use of descriptive and persuasive language help depict the brutality of black torture. In her published work Lynch Law in All Its Phases (1893), Wells-Barnett explains how black people were murdered without question:

"In 1886, a white woman died of poisoning. Her black cook was suspected, and as a box of rat poison was found in her room [... when the cook was] dragged out of jail, every stitch of clothing torn from her body, and she was hung in the public court-house square in sight of everybody [...] the State Supreme Court holds its sittings there; but no one was arrested for the deed, not even a protest was uttered. The husband of the poisoned woman has since died a raving maniac, and his ravings showed that he, and not the poor black cook, was the poisoner of his wife.4" This shows how black people were never given the chance to prove their innocence. Furthermore, she writes about the unfairness that the “simple word of any white person against a Negro is sufficient to get a crowd of white men to lynch a Negro.”5 Wells-Barnett explains the egregious nature of lynching and multiple cases when such tragedies occur. Her reports invoked critical analyzation and drew attention to this issue.

Working in the 1890s, Wells-Barnett faced many threats and vandalization—forcing her to move twice with her husband, Ferdinand Barnett, to escape danger.6 Regardless, Wells-Barnett continued her controversial work proving that “lynching was a form of racial violence aimed at ambitious black southerners.”7 Within the first page of Wells’ Lynch Law in Georgia, she writes that the “real purpose of these savage demonstrations is to teach the Negro that in the South he has no rights that the law will enforce.”8 By writing reports on the gruesome demonstrations and exposing the corruptness of letting these acts occur, Wells-Barnett stirs conversation and willingness to limit lynching.

Although not accepted by other white women suffragists for her race, Wells-Barnett founded the first of many black women organizations that focused on civil rights and suffrage issues: National Association for Colored Women, Chicago’s Alpha Suffrage Club, and Ida B. Wells-Barnett Club.9 Impacting many, she contributed to newspapers and journals, organized meetings and gave speeches worldwide, and published detailed reports. Passing away on March 25th, 1931, Ida B. Wells-Barnett was a remarkable woman who never stopped pursuing her goals for the abandonment of lynching and for black civil and political rights in America.

SOURCES +

What the Project Means to Me

From breaking barriers, being resilient and uncompromising on their right to vote, Ida B, Wells, my grandmother and my aunt all have been interesting to research about. I learned how Wells was determined in her pursuit to abandon lynching and fight for black rights in America. Even through family trauma, Wells found her passion and never gave up on her goals despite large-scale resistance. I was also fascinated to learn about my grandmother’s history. From family testimonies, I realized that my grandmother was a political woman during her time; despite the lack of politically active women around her, my grandmother strove to enfore her right to vote in India.

Similarly, in the 1970s, when my father’s family immigrated to America, my aunt was the only woman in her family the right to vote. When she was of age, she did not flee on her opportunity to represent brown, Muslim, women within elections. This was a connection that I saw through my research between Wells and my own history; both Wells and the important women in my life stood up as minorities to make sure that their voices were heard; something minorities today need to keep in mind for future elections. I found it beneficial to connect my own family experiences to history because it gave context and meaning to my family members’ actions. For example, even though going to a voting poll and casting a vote might seem simple, in 1960s India, this action was much more complicated for women. This allowed me to understand the work that my grandmother went through just to accomplish this task that may seem simple today.

Another benefit of connecting my history to a larger view was that I was able to see the importance of minority women standing up for what they believe in and being uncompromising in what they want; their actions also allow us to enjoy and have today privileges that we take for granted—like voting. More than ever today, it is necessary to be uncompromising; this is something that I will remember when I attend rallies, call representatives, and cast my vote. As an Indian American Muslim woman, the level of intersectionality is complex but not unusual. It is necessary for communities to come together and educate ourselves on the situation of our country and how we can change its future for the better. Voting is important, and minorities votes are beneficial in numbers. Government elections shape our future and we need to make sure that national issues are being addressed and that representatives are listening when we are uncompromising in our goals.

Explore the Archive

More From This Class

Click on the thumbnails below to view each student's work.Deadline Extended

There's still time to join Women Leading the Way.

Become a part of our storytelling archive. Enroll your class today.

Join the Project