Amanda Renzi & Catherine Carpio

Townsend Harris High School | Flushing, NY | 11th Grade

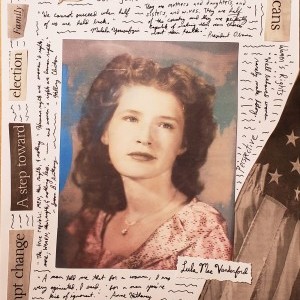

Inspirational Family Member

Eva, My Paternal Grandma

My paternal grandma, Eva, was the first woman of my immediate family to vote in the US. As an immigrant, she came over in her 30s and while working she would hear about the political climate through her employers and the media. Back in her birth country, Guatemala, she did not go out to vote as she spent most of her time running the family grocery store and taking care of her five children; it should be noted that she would have been able to vote as women’s suffrage in Guatemala passed when she was 9 years old, in 1946. Often times, the poll stations were not close by and my grandfather would not go out to vote either.

When my grandma Eva came over, it was the 1970s and the 19th amendment had been ratified for over 50 years. She came to the US a few years after becoming widowed and went to live in upstate New York, mostly working in order to send back money to her children. In these early years in the US, she recalls that she did not pay much heed to the political climate but as time passed her interest grew. She recalls the controversy of the Vietnam war and whether or not it was a necessity; and hearing discussion from her employers on the topic of how Watergate had gone down but not really understanding what it meant. What started to call her to the polls was talk of the Cold War as well as the “nuclear freeze” agreement of the 1980s.

While she did not partake in fighting for women’s right to vote like Hubertine Auclert, today she always makes time to vote, at the very least for major elections, as she believes that every vote represents a voice and that everyone who lives in the country should use that voice.

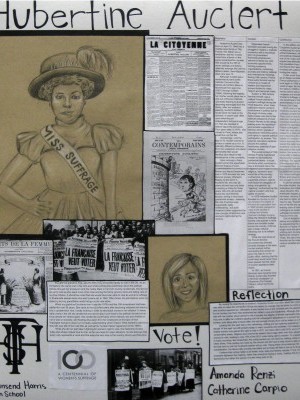

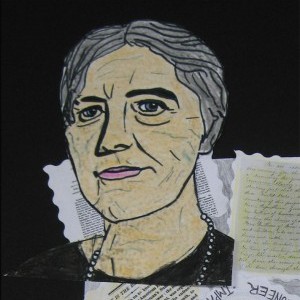

Historical Figure I Admire

Hubertine Auclert

Hubertine Auclert was born on April 10, 1848, in a middle-class family in Tilly, France. Her father was a landowner and her mother came from a family of the same social position. She would be the fifth of seven siblings and lived a relatively average life until her father’s death when she was 13.

Although Auclert was a residential student at the Catholic Convent of the Dames de l’Enfant Jesus in Montmirail from age nine (1857) through sixteen (1864), following the tragedy, her mother would place her in and out of Roman Catholic convents — leading to Auclert to becoming estranged from the family. After her mother’s passing, Auclert’s brother would send her back to the convent. It wasn’t until 1869, upon inheriting an independent fortune at age 21, that she decided to forever leave the convent. Four years later, in 1873, she moved to Paris, where she would live out her life.

Interestingly, until the age of 16, Auclert wished to pursue a career as a nun. A radically different profession from her outspoken anti-cleric personality that would develop as a result of her adolescence in the convent. Upon arriving in Paris, Auclert joined the leading feminist league of Léon Richer and Maria Deraismes, and in 1876, founded her own feminist society, “Women’s Rights.” At this point in Auclert’s life, she was 28 years old and had only been residing in Paris for three years. Not only did Auclert found her own feminist society during a very patriarchal society but such initiative further supported the new concept of feminism and women’s rights during the century.

CONTEXT

Organized French feminism sprouted during the struggle, to replace a Catholic monarchy with a republican form of government. Feminists emphasized reforms in family law and economic opportunities, forming numerous organizations, publishing journals and holding national and international meetings. During 19th century France, these early feminists can be viewed as a mosaic of leaders and respective groups divided by class, religion and personal rivalry.

Auclert, a 19th century feminist herself, was a militant French activist for women’s suffrage during the Third Republic, when many politicians feared women’s involvement in politics due to the angst of losing votes. Said unease was due to the believed allegiance of most French Women to the clergy, leading even republican and socialist supporters of feminist reform (people of educational institutions and in civil rights) to oppose political participation by women. This external opposition centered on the political reactionary potential of said religious women.

The social context of 19th century France maintained women to the traditional patriarchal family – a social structure which continued to play a dominant role in the religious, economic and social life of the country. Furthermore, those who supported women’s right to work faced the allegation of being anti-patriotic by “rejecting” motherhood as the ‘natural vocation’ and only career of women.

In 1876, Hubertine Auclert founded the Société Le Droit des Femmes (The Rights of Women Society) an organization that in 1883 formally changed its name to the Société Le Suffrage des Femmes (Women’s Suffrage Society). While the Women’s Suffrage Society was popular in more liberal and socialist circles across the country. It did not gain a large national following due to its militant strategy. While the main focus of the French feminist movement was directed towards changes to the laws, Auclert pushed further, demanding that women be given the right to run for public office, claiming that the unfair laws would never have been passed had the views of women legislators been heard. In 1881, as French feminism laws became more liberal, Auclert also founded a feminist newspaper La Citoyenne (The Female Citizen), which ran for ten years.

CONTRIBUTION

In the edition of La Citoyenne, Auclert argued vociferously for women’s enfranchisement, with full civil and political citizenship being one of her major aims. She argued that eliminating half of the population from voting, and hence from being directly involved with politics, was hurting the nation.

In her youth, Auclert ran as an illegal candidate for French Parliament in 1885, and again in 1908 at 60 years of age. By the turn of the 20th century, Auclert had an active role in the feminist congress and revived Women’s Suffrage. In 1904, she would lead a militant demonstration to burn the French Civil Code.

At 60 years of age in 1908, Hubertine Auclert led a suffragist parade through Paris, and on that Sunday afternoon during the Parisian municipal elections of 1908, earned the appellation “The French Suffragette.” She made her way into a poll, walked to a table where men were depositing their paper ballots in a wooden box and before stunned officials, she seized the ballot box, smashed it to the floor, and stamped on the spilled ballots. Her arrest would come after a brief speech denouncing “unisexual suffrage.” At her subsequent trial, she proudly accepted the comparison to the “violent suffragettes” of Britain and vowed to continue the struggle to win the vote.

It can be concluded that the older Auclert, the more outspoken and militant her views became. She eventually stopped paying her taxes, claiming that since she had no rights, she did not need to pay. Towards that end of her life, she remained a leading voice of militant suffragism as the moderate suffragist movement grew in France (1910-14).

One of Auclert’s most lasting accomplishments may be popularizing the word ‘feminist’ in France. With this single word, she gave a unifying term to people fighting for women’s rights. Today, the use of the word feminist can be noted in various societies around the world.

What the Project Means to Me

By having the opportunity to research Hubertine Auclert and learn about her motivations, I was able to make the connection of how the desire for change may be driven by one’s personal and youthful experiences. Ultimately, it was Auclert’s time in the convent and the abandonment by her brother that awakened her militant voice and leadership. Although she would talk with her mother about women’s role in society, the degree of female oppression would only truly sink in after her mother’s passing and her subsequent abandon in a convent by her own brother; only being able to leave after she had enough money so as to not be reliant on a husband.

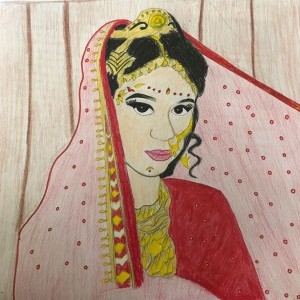

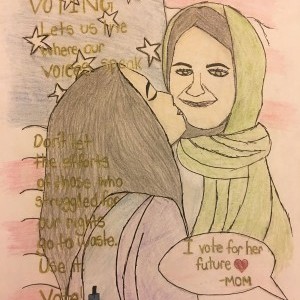

Looking into the past was a very refreshing, chilling and eye-opening experience. Many issues of the past are still present today in many countries and societies. For instance, in Saudi Arabia, women only gained the right to vote in 2011, and in Pakistan’s conservative areas, religious and community leaders discourage other men from allowing women to vote, leading to only 10% of the 2013 votes being cast by women. To a lesser degree, in many countries like Guatemala, the voting centers are not close by, making voting a burden. Other times, if the centers are close by, the women still have to stay home to take care of the kids and so only the husbands go vote. Taking these circumstances into consideration, the democratic process has failed and at times still fails to live up to its grandeur.

I believe that voting matters at all levels, local, state and federal, equally. If only one group of people represent the majority, rather than everyone having a voice, I believe this to not be democracy but rather the opinion of a few being past on to all.

Explore the Archive

More From This Class

Click on the thumbnails below to view each student's work.

Vivian Chen, Josephine Chen, Ivan Chan, Zafirah Rahman, Neeharika Reddy, Daniel Shi, Daniel Shi, Jacqueline Cho & Osiris Guerrero

Jennifer Moran, Adebola Ademola, Julia Hong, Vicki Kanellopoulos, Inga Kulma, Maimunah Virk, Deborah Molina & Kailey Van

Kristina Chang, Sarah Chowdhury, Bethany Leung, Letian Fang, Cathy Choo, Kelly Chan, Emily Tan, Adamary Felipe & Kenney Son

Deadline Extended

There's still time to join Women Leading the Way.

Become a part of our storytelling archive. Enroll your class today.

Join the Project