Paloma Figueroa

Lycée Français de New York | New York, NY | 9th Grade

Inspirational Family Member

Aida Villafañe

Before society began pushing towards gender equality in the workplace, it was a real struggle for women to be taken seriously and respected for their work in certain domains, particularly in the male-dominated scientific field. In “a time when institutional barriers to a woman’s promotion were much greater than they are today, and when many universities did not allow women to rise to the rank of full professor or senior scientist”, my grandmother, Aida Villafañe, and American microbiologist Alice Catherine Evans were no exception to these struggles. However, despite the obstacles they faced as women working in a field of men, both were able to succeed as scientists during a time when few women were able to do so. This project is an homage to them, as well as to all the other pioneering female scientists who paved the way for girls in STEM today, and whose names are often overshadowed by those of their male counterparts.

First, I am grateful for the biographical book, Women in Microbiology, edited by Rachel J. Whitaker and Hazel A. Barton for providing me with information to complete this narration. Now, onto the first woman.

Dr. Aida Villafañe was born in Fajardo, Puerto Rico on February 9, 1924. She was a skilled pianist and a hardworking student throughout her youth, graduating high school in 1941 as Valedictorian of her class. She started college at the University of Puerto Rico in San Juan but transferred on her second year to Barnard College of Columbia University in New York City. While in college, she developed an interest in Microbiology and her professor encouraged her to follow her studies at Cornell University in Ithaca, NY. The Masters program typically was 2 years long, but Aida decided to finish it in one year, because of the cold weather on campus. She earned her Masters degree in microbiology in the early 1940s and then returned to the University of Puerto Rico, where she taught microbiology to future scientists. In 1949, Aida went to study at the University of Pennsylvania to earn a PhD in microbiology, which lasted 2 years. During her time at UPenn, she met her future husband, my grandfather, who is also from Puerto Rico and was in his third year in medical school at the time. They both graduated in 1951, she with her PhD and he with an MD degree. They then parted ways, as Aida returned to San Juan to continue teaching at the University of Puerto Rico and my grandfather stayed for an internship at the Pennsylvania Hospital, and later his three-year-long residency in Urology at UPenn. A few years later, Aida returned to Philadelphia and began working at Wyeth, a pharmaceutical company specialized in the production of Penicillin, one of the first antibiotics on the market to be effective against many bacterial infections. In 1954, she was sent to the Wyeth-Fontura Pharmaceutical Co. in Sao Paulo to work on setting up a lab to start the production of Penicillin for commercial use. After a successful and interesting year in Brazil, Aida returned to Philadelphia and met with my grandfather. They decided to get married shortly after and returned to Puerto Rico together, where he started work as a urologist and she began working at the Department of Microbiology of the University of Puerto Rico Medical School.

Years later, following my grandfather’s service in the army in Germany, him and my grandmother returned to San Juan, where they settled down in their new home and had 3 children, two sons and one daughter. When she became a mother, Aida stopped working as a microbiologist in order to devote her full time and attention into raising her children, which she did with great love and discipline. In addition, she became an active member of her community in the artistic and social fields. Amongst other things, she and my grandfather helped in collecting funds for the Heart Association, and directed the First, and very successful, American Cancer Fundraising Year. Aida also was a great help to her husband in his practice of medicine: she helped him at his offices and wrote a yearly notebook with multiple listings of the patients seen, their insurance coverage, payments and billings.

As described by my grandfather, Aida Villafane was a loving and helpful wife, very intelligent, and a wonderful mother and grandmother. Sadly, she passed away in August of 2011, before I got the chance to spend much time with her and get to know her well. However, she lives on in my family’s memory as a strong, elegant and intelligent woman, able to forge a career as a microbiologist during a time when few women were able to do so.

HISTORICAL FIGURE I ADMIRE

Alice Catherine Evans

Some of you may know Alice Catherine Evans as the first professionally successful female microbiologist, who paved the way for all succeeding female microbiologists and led other scientists, mostly male at the time, to recognize and accept the validity of scientific research conducted by women, before women were even given the right to vote. She was the first woman to hold a permanent appointment as a bacteriologist at the US Department of Agriculture (USDA), the first woman to hold a senior appointment in the US federal government and the first female president of what is now known as the American Society for Microbiology. Born on January 29th, 1881 on a farm in Pennsylvania to a religious and hardworking family, Alice always highly valued education. After graduating high school, she taught grades 1 through 4 in a nearby school, as teaching was the only profession available to women at the time. However, this profession did not suit Alice’s interests, and so she quit and joined a 2 year course about science and nature at the College of Agriculture at Cornell University. The course was free of cost, which drew Alice in, as she didn’t have much money. Once the course was completed, Alice’s interest in sciences had grown so much that she chose to remain at Cornell to study science. Her lack of money prevented her from studying the more costly sciences, and so she took the only science free of tuition that Cornell had to offer: bacteriology. Alice continued to work very hard, devoting all her free time to her studies and even working part-time as a housekeeper, and helping out in the alumni library. In 1909, at the age of 28, Alice completed a bachelor of science in agriculture and one year later, became the first woman to complete a bacteriology scholarship at the University of Wisconsin, and received a master of science degree. With the help of her professor at the University of Wisconsin, Alice became the first woman to acquire the position of federal civil employee as a bacteriologist in July, 1910. She wished to investigate better and healthier ways of making cheese, and conducted her research at the University of Wisconsin Dairy Division for three years. She then unwillingly moved to the US Department of Microbiology building in Washington, DC. It is said that USDA officials nearly fell of their chairs when they heard that a woman scientist would be joining them. At the USDA, she studied the bacteria of freshly drawn milk from cows and strongly advocated for the pasteurization of cow’s milk. Alice received some backlash for publishing her research on the effects of drinking raw cow’s milk: she had discovered a bacteria in the milk of certain cows, causing abortion in cows and Malta Fever in humans. Although later found out to be correct, these findings were not deemed accurate at the time, coming from a woman, especially because no male scientist had noticed them before. Even respected bacteriologists rejected Alice’s work, most likely because her papers on pasteurization were published in 1918, two years prior to women being given the right to vote. In 1918, when most male scientists were drafted for World War I, Alice joined the Hygienic Laboratory, later known as the Public Health Service. This transition allowed her interest on Brucella, an infection spread from animals to people by unpasteurized dairy products, to expand.

In 1922, Alice became infected by brucellosis, a respiratory infection causing undulant fever, and had to remain at the hospital for weeks. Despite her health condition, Alice continued her work at the Hygienic Laboratory, and in 1926, was invited to serve as a member of the Committee on Infectious Abortion of the Federal Department of Agriculture. Two years later, in 1928, Alice was elected president of the American Society for Microbiology, becoming the first woman to hold this position.

Shortly after, while pasteurization was still a controversial topic, people started accumulating evidence supporting Alice’s conclusions on the spread of bacteria in raw milk. In 1934, the Federal Program for the Eradication of Brucella began, mandating that cows be tested for Brucella, and if infected, be slaughtered. About 30 years later, all United States state governments voted to pass a law requiring all commercial milk to be pasteurized, thanks to Alice’s research on raw cow’s milk and the cause of brucellosis.

Even after her retirement in 1945, at the age of 64, Alice continued to be involved in the fight against brucellosis and campaigned for a better diagnosis of the disease. She also spoke out and was passionate about the subject of females entering male-dominated careers, and was always supportive of women. She once said, “Women have proved that their mental capacity for scientific achievement is equal to that of men. Women do not receive the same recognition as those of men.” Alice received many awards and recognition in her later years. She was, amongst other accomplishments, included in the biographical book “Profiles of Pioneer Women Scientists”, was elected to the National Academy of Science as well as the National Women’s Hall of Fame, received an honorary medical degree, and was honored as one of the four “Mount Rushmore” faces of microbiology.

Known as the Mother of Pasteurization in the United States, Alice is remembered as a pioneering American microbiologist and a brave, sophisticated, intelligent woman.

What the Project Means to Me

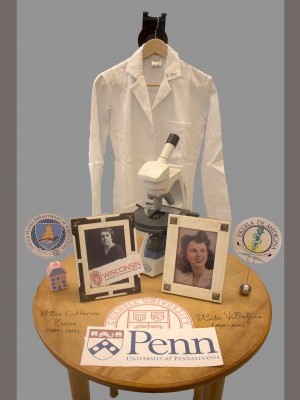

Double portrait of my grandmother, Dr. Aida Villafañe, and Alice Catherine Spence.

Deadline Extended

There's still time to join Women Leading the Way.

Become a part of our storytelling archive. Enroll your class today.

Join the Project