Jane Bayard Curley

Freelance Curator

Florence speaking at a rally, courtesy the Library of Congress

Florence speaking at a rally, courtesy the Library of Congress

My great aunt, Florence Bayard Hilles, was the black sheep of our family. She was also my hero. It was her tattoo that hooked me.

Whenever I quizzed my grandmother about her, there was an eye roll. “Oh, Florence! She had a tattoo on her arm. A suffragist tattoo.” Aside from that tantalizing detail, all I could find was that she was married to a lawyer, she raised dogs, and she left her house to the local fire department when she died so they could burn it down for practice. It was not until I was an adult that I learned Aunt Florence’s real – and impressive - story.

Florence in full “feathers and fans"Born in 1865 into one of Delaware’s most prominent political families. Aunt Florence’s father, grandfather, great-grandfather and brother were all US Senators. She was the daughter of the thirtieth US Secretary of State, Thomas F. Bayard, who later served as Ambassador to the Court of St. James. She was presented to Queen Victoria in full “feathers and fans" (as the invitation read) in 1893.

Florence in full “feathers and fans"Born in 1865 into one of Delaware’s most prominent political families. Aunt Florence’s father, grandfather, great-grandfather and brother were all US Senators. She was the daughter of the thirtieth US Secretary of State, Thomas F. Bayard, who later served as Ambassador to the Court of St. James. She was presented to Queen Victoria in full “feathers and fans" (as the invitation read) in 1893.

In 1913, while showing dogs at the Delaware State Fair, she heard Mabel Vernon giving an impromptu speech. It was a life- changing meeting. “Mrs. Vernon is saying what I believe in and I’m not doing anything about it,” was Aunt Florence’s response. At that moment, the debutante and dog breeder became a passionate, lifelong activist. Aunt Florence traveled for the suffrage cause, working wherever she was needed.

In 1916, she crossed the country on a speaking tour, ending in Seattle where she rented a float plane and scattered pamphlets over the city below (see illustration, "Florence speaking at a rally"). She even donated her car to the cause, dubbing it “The Votes for Women Flyer.”

Along with Mabel Vernon, Florence heckled President Wilson in 1917, shouting – before they were forcibly removed - “What will you do for woman suffrage?” On July 14 that same year, she was one of sixteen Silent Sentinels arrested for picketing in front of The White House. In the shabby courtroom, facing charges of obstructing traffic, she remarked, “Well, girls, I’ve never seen but one court in my life and that was the Court of St. James. I must say they’re not very much alike!” All sixteen refused to pay the $25.00 fine and were sentenced to sixty days in Occoquan prison in Virginia. They were pardoned after three days. Undeterred, she was again prominent in the Watch Fire demonstrations at the White House in 1919.

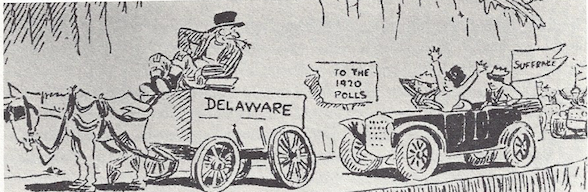

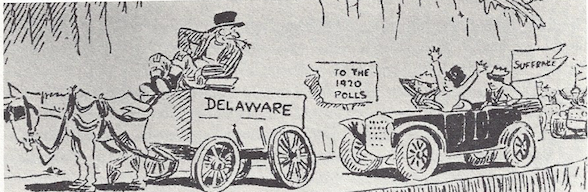

Suffragist cartoon, 1920

Back in Delaware, on March 25, 1920, she and Carrie Chapman Catt were featured speakers – along with President Eamon de Valera of the Irish Free State - before the state legislature. Knowing they were at least a half dozen votes short, the “suffs” resorted to kidnapping the man who was designated to present the suffrage amendment, whisking him away in the Votes for Women Flyer. It was in vain: the amendment was defeated anyway. Aunt Florence moved on to work for the vote in Tennessee, the state that won the honor of being the final one needed to ratify the Nineteenth Amendment.

After the amendment passed, Aunt Florence continued to be active in politics. She was a founding member of The National Woman’s Party, serving as its chairman from 1933-1936. She also founded the library at the Sewall- Belmont House and Museum in 1943, the oldest feminist library in the United States. It is named after her. She was an advocate of the proposed Equal Rights amendment, and worked for the National Committee for Planned Parenthood.

She died in 1954.

To her relatives, she was an embarrassment; contrarian and rebellious. During WWI, when her family accused her of being unpatriotic because she put suffrage before support for America’s allies, she took a dangerous job in a local munitions factory to prove them wrong. That took guts, but she never lacked them.

To me, she was the first woman brave enough to carry on the family’s tradition of public service and to speak her own truth. Writing to Florence in 1941, Alice Paul concluded, “I take you as my model and try to be as gallant and generous and courageous as you are. I could wish for nothing more.”

Whenever I quizzed my grandmother about her, there was an eye roll. “Oh, Florence! She had a tattoo on her arm. A suffragist tattoo.” Aside from that tantalizing detail, all I could find was that she was married to a lawyer, she raised dogs, and she left her house to the local fire department when she died so they could burn it down for practice. It was not until I was an adult that I learned Aunt Florence’s real – and impressive - story.

Florence in full “feathers and fans"

Florence in full “feathers and fans"In 1913, while showing dogs at the Delaware State Fair, she heard Mabel Vernon giving an impromptu speech. It was a life- changing meeting. “Mrs. Vernon is saying what I believe in and I’m not doing anything about it,” was Aunt Florence’s response. At that moment, the debutante and dog breeder became a passionate, lifelong activist. Aunt Florence traveled for the suffrage cause, working wherever she was needed.

In 1916, she crossed the country on a speaking tour, ending in Seattle where she rented a float plane and scattered pamphlets over the city below (see illustration, "Florence speaking at a rally"). She even donated her car to the cause, dubbing it “The Votes for Women Flyer.”

Along with Mabel Vernon, Florence heckled President Wilson in 1917, shouting – before they were forcibly removed - “What will you do for woman suffrage?” On July 14 that same year, she was one of sixteen Silent Sentinels arrested for picketing in front of The White House. In the shabby courtroom, facing charges of obstructing traffic, she remarked, “Well, girls, I’ve never seen but one court in my life and that was the Court of St. James. I must say they’re not very much alike!” All sixteen refused to pay the $25.00 fine and were sentenced to sixty days in Occoquan prison in Virginia. They were pardoned after three days. Undeterred, she was again prominent in the Watch Fire demonstrations at the White House in 1919.

Suffragist cartoon, 1920

Back in Delaware, on March 25, 1920, she and Carrie Chapman Catt were featured speakers – along with President Eamon de Valera of the Irish Free State - before the state legislature. Knowing they were at least a half dozen votes short, the “suffs” resorted to kidnapping the man who was designated to present the suffrage amendment, whisking him away in the Votes for Women Flyer. It was in vain: the amendment was defeated anyway. Aunt Florence moved on to work for the vote in Tennessee, the state that won the honor of being the final one needed to ratify the Nineteenth Amendment.

After the amendment passed, Aunt Florence continued to be active in politics. She was a founding member of The National Woman’s Party, serving as its chairman from 1933-1936. She also founded the library at the Sewall- Belmont House and Museum in 1943, the oldest feminist library in the United States. It is named after her. She was an advocate of the proposed Equal Rights amendment, and worked for the National Committee for Planned Parenthood.

She died in 1954.

To her relatives, she was an embarrassment; contrarian and rebellious. During WWI, when her family accused her of being unpatriotic because she put suffrage before support for America’s allies, she took a dangerous job in a local munitions factory to prove them wrong. That took guts, but she never lacked them.

To me, she was the first woman brave enough to carry on the family’s tradition of public service and to speak her own truth. Writing to Florence in 1941, Alice Paul concluded, “I take you as my model and try to be as gallant and generous and courageous as you are. I could wish for nothing more.”